|

The Christchurch Civic

Creche Case |

|

|

|

|

|

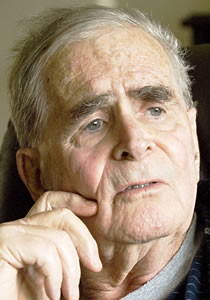

MARK COOTE/Sunday Star Times FRANK'S FAREWELL: Frank Haden has

written his last newspaper column, forced out of print after 50 years by the

prostrate cancer which is slowly killing him. Frank Haden has written his last newspaper column, forced out of print

after 50 years by the prostate cancer which is slowly killing him. He talks to

Rosemary McLeod. "What they don't appreciate

is that I'm always right!" Flashes of the great, provocative Frank haden

are still gloriously there, but this is a Frank enetering the final stages of

cancer, his edge and memory blunted by morphine. His illness has become the

veteran journalist's final story, though he'll never write again. Few people have known about

Frank's prostate cancer, which he has lived - and worked - with since it was

diagnosed in 1998. Those who know him will understand that he'd want to tough

it out, and would shrink from the prospect of pity, but the time has come

when even the effort involved in sitting at a computer has become too

painful. His cancer spread into his bones

five months ago, and tomorrow Frank will be asking his doctor direct

questions he has so far avoided; questions such as, "How long have I got

to live?" and "Can you really help me manage the pain if it gets

worse?" He has lived six years longer than

was first predicted. "My specialist applauds the

columns I write, thereby demonstrating his superiority at every turn, and

says the protracted delay in things turning bad means somebody up there

wanted me to go on writing. That sort of ego massaging is music to my

ears!" His specialist was not alone in

reading Frank, though not everyone agreed with him. Frank attracted more

letters to the editor than any other columnist in this newspaper in his 17

years of writing for it and its forerunner (and well over 50 years in

journalism). He has listed his favourite issues

as "The Iraq invasion, the persecution of Ahmed Zaoui, compensation for

uncontrollable thugs, euthanasia, prostate cancer screening, anywhere/anytime

speed cameras, quack medicine, the excesses of the Treaty industry, Parole

Board decisions, nuclear power, global warming myths". He has claimed that he doesn't

U-turn on his views: "I spend a lot of time saying `I told you so!'

after being proved right." Frank now tells even his final

illness as a story, one involving a challenge to the health system. It's a

matter of getting the facts right, of making complicated technical matters

simple to understand, of being logical - all attributes he would expect from

well-crafted news. "There's quite a liberal

amount of tumour material pasted on the third and fourth vertebrae - looking

rather like Vegemite on toast," he explains. It's for this reason that

he now lives between a brown leatherette La-Z-Boy armchair and a hospital bed

set up for him at home, his elbows padded to avoid pressure pain, swallowing

his way through a medical menu of 30 pills a day. Maybe we always believed Frank was

indestructible: he has, after all, been writing energetically up to the age

of 76. Certainly his age never counted against him; he was 61 when he was

sent to Auckland from his long-time Wellington base to try to save the doomed

Auckland Star. There was, he concedes, no future for afternoon papers, and he

now doubts how genuine its management's intentions were. "The number of times I nearly

killed myself in the service of INL (Independent Newspapers Limited). "In 1992, I neglected what

was obviously a very bad case of the flu because I was doing things that had

to be done, and I fainted. I had pneumonia. I've had a shadow on both lungs

since then, and I was told on no account to get the flu again, or it would be

the end of me. I've always felt aggrieved that nobody appreciated these

efforts." The irony is not lost on Frank

that he's dying of a disease which is detectable by regular screening, and

which he argued the case for in columns well before he became ill. "It was the basis of a

terrible fight I had through the column in 1993 with Karen Poutasi and the

Ministry of Health, on the need for all men to be tested regularly. "It's a simple examination,

it costs bugger-all, and it involves no pain. "I've made as much of a fuss

as I can about the need for men to be tested for prostate cancer, and now

here I am with prostate cancer which would have come to light if I'd been

part of a screening process. "The Ministry still won't see

reason. They've got a completely lunatic idea that women are much stronger

than men; it doesn't matter if they're given a fright and told they've got

uterine cancer or breast cancer... Whereas men being weak vessels are unable

to stand the strain and trauma of a warning that they could have cancer. It's

an insane assumption that men and women are different in that insulting way!

I mean, for God's sake!" We who have worked with Frank know

well the way he builds his arguments, lacing logic with absurdity, and

sometimes defending both with equal vigour. Not for nothing was he known in

the trade for the past 25 years as Mad Frank. Although he has always deplored

the use of exclamation marks, his own speech is peppered with them like

buckshot, often pointing up his more outrageous assertions. Colleagues on the

Dominion once collected them into a slim volume of quotations designed, for

the most part, to appall. He has been gleefully

anti-feminist, anti-Maori activist, and anti-liberal. Frank is unsure, now, of exactly

when he began column writing after a career which culminated in the

editorship of two newspapers (the Sunday Times and the Auckland Star). "It was (Geoff) Baylis' idea,

when he was editor of the Dominion, that I should be doing a weekly

trouble-making column. I corrected him when he said a weekly right-wing

column. I said I'm simply NOT a right-winger. I hold a lot of inflammatory

ideas that might seem to some people to be right-wing, but I'm not at all.

Stripped to bare necessities I'm quite a compassionate kind of person, so long

as people are prepared to take a fair measure of responsibility. "I lose patience quickly with

people whose first port of call is to say, 'It's not my fault'. To people who

say that, I say `It bloody well IS your fault!' I've had an astonishingly

hard life in a lot of areas and never felt that I had to lie on the floor and

wail about what a rough time everybody's given me. I'm not like the Parnell

Panther, moaning about being in a dog kennel!" (Mark Stephens, the

rapist known as the Parnell Panther, has described being kept in a dog kennel

when he was a child.) Frank was

born in 1929, the year of the Wall St stockmarket crash that heralded the

Great Depression. This, and another great misfortune of his young life, must

have shaped his view of the world. "Yes, I have memories of the

Depression. Bread and dripping -which I quite like, actually. Dripping is

much nicer than butter! "My father was an Englishman

who came here in 1926 to sell motorbikes. He had a shop in Manchester St in

Christchurch. "My father used to race on

weekends, but under sufferance, because if he wanted to sell motorbikes, he

had to be seen flogging them about in the sun... I used to be there on

Saturday mornings smelling the petrol, as they used to race and go for

records, and I did a bit of racing myself later. "I've got sound stories that

are nothing but exhaust noises - of the Isle of Man and other races; some

just recording an Aston Martin on a test bed. These would be played when we

had a little holiday home in Martinborough. We'd sit and listen to motorbike

exhaust noises. It's the nicest noise there is, a very loud exhaust noise!

That's why I get furious with television, because what comes out when they're

transmitting motor races is not exhaust noises but techno, the worst noise

that humanity has ever perpetrated!" Frank has owned motorbikes on and

off for most of his life, the last a Honda 400 which took him to his office

and back in the past few years. "A light bike, certainly nothing

glamorous or remarkable or romantic or exciting" - as opposed to his

favourite bike, the BSA Clubman 350cc he once raced. It may seem paradoxical - as much

about Frank is - but his other great listening love is Bach. "There are

two great categories of music. Bach is one category, and everyone else is the

rest." Frank's mother hoped that his love

of the mechanics of language, and of argument, would lead him into law, but

that didn't last, any more than did his Catholicism. "Once you start to see

through bullshit then you see through all bullshit," is how he has

explained his disillusionment with the church - leveraged into a lifetime's

disillusionment with all authority, even newspaper proprietors'. Frank

credits his many years as a sidelined senior newspaperman to his refusal to publish

"lying" apologies to the Press Council when it found against him. "I was a law clerk, 19, and

the smell of dusty files drove me across the street to the Press, where I

took a job for exactly 25% of the previous salary. I had to hang about and

wait until I was 21, when you were no longer able to employ people for

nothing. I have to thank an extremely indulgent and self-sacrificing mother.

At that age I should have been contributing to an orphaned household, and it

was the end of her dream of me being a lawyer. Law was a prestigious

activity, and far better paid." There is more to that story; the

death of Frank's father when he was still at college, and his youngest

brother had only just been born. A simple hernia operation ended in tragedy

because doctors believed at that time that patients should not stir from

their beds after abdominal surgery. Frank's father developed a blood clot

from lying in bed, and never came home. His mother was left alone with six

children. "I was summoned by the rector

(of St Bede's College) and told in the quadrangle that I'd better go home

because my father had died, which I didn't take very kindly to because I was

fonder of him than I had realised. Once I figured it was a useful thing to

do, I did actually weep. Until then I'd thought that weeping was a bit like

real men and quiche. "The family got by with

EXTREME difficulty, because that was at a time when they stopped the pension

as a penalty for accepting what my mother had every reason to regard as her

right. Her father had died and left her enough money to get a new roof on the

house, and get other jobs done to put the family home put in good order. "The Public Trust officer

handling her case didn't know, and the Public Trust office didn't tell him,

that if he gave my mother all this money in one year, that would be over some

arbitrary limit. They said nothing, then when they had handed over the money

they told her that her pension would now stop for the next 12 months! So in

addition to being at school, for the next 12 months I had fulltime labouring

jobs - in a brickyard and as a carpenter's labourer - and I also did a stint

in the freezing works. "Luckily it was a time of

full employment. I was as big then as I am now, so my holding down a male job

like this didn't worry anyone. Also, several very kind neighbours admired the

way my mother was coping, and made sure I got jobs. I had to give up my

bedroom and move out to the verandah, and the room was taken over by two

boarders, whose contribution was absolutely vital. We had to have that

money." It's tempting to find in Frank's

early experiences an explanation for his dogged sense of duty and loyalty,

learned no doubt when he became the sole support of his family. His marriage

to his tolerant wife Merle, too, has lasted 50 years, producing four

daughters and seven grandchildren. He has confessed to regrets that he put

work before his family, and often quotes his wife's dry observations on his

failings in that area. I remember him rather proudly claiming that Merle said

if one of their children was run over, he'd call a newspaper before he called

an ambulance. The urge to challenge authority

figures, one that marks any good journalist, may well have emerged after the

death of his father from medical misadventure, and witnessing the

bureaucratic callousness towards his recently widowed mother. Maybe, too,

that willingness to work hard, and admiration of his striving mother,

unleashed his columns on welfare dependency. "Very, very rarely have I

been writing just to provoke," Frank says. "My columns were

virtually always written because I felt something quite deeply; I very rarely

stitched something together knowing I was out of line for the best of

reasons. So many of my columns infuriated people who couldn't understand why

I'd taken this particular line when in fact I'd bloody well meant it! I'm not

a tongue-in-cheek writer at all." Frank now talks about what he

calls the end of the world, his concern that the planet will use up its

resources in the next 50 years. "We're deep in the shit. It takes a lot

for me to say that, but we are. The picture we have is of the

apocalypse." Is this a parallel for his

situation? "The coincidence has not evaded me." It's hard to ask a man as quixotic

and wilful as Frank just how serious he has really been, with statements like

his oft-quoted, "I am always right!" Reluctantly, Frank admits he

has been pulling everyone's leg at least some of the time. "Of course

nobody can be always right, but people jump when you say it!" And do you like that? There's a

long pause. "Yeah. I would have to admit I'm a deliberate provocateur,

because that's what making people jump is. I'm reluctant to admit it, because

it's pushing me hard on to admitting a substantial character flaw."

Namely? "Insincerity." What makes a good columnist? "To be a good columnist you

have to be a journalist to begin with, and a good columnist is one who won't

take yes or no for an answer. I would not want to be pompous about the role.

It's to produce material at regular intervals that you hope will keep people

interested enough to keep the editor buying it. "You can be a perfectly

adequate journalist without being a columnist. A lot of people TRY to be

columnists, and you can feel them, like monks in The Da Vinci Code, lashing

themselves into producing a column they don't want to produce at all. If

you're a columnist it runs easily once you get started, but there are a lot

selling a column a week who are obviously not sold on the idea at all." In the end, does journalism

matter? "Of all the possible human

activities, journalism matters more than most, because it interprets the way

things are for people who've got ears to hear, and eyes to see. If not for

journalism the world would be a meaningless sort of place. We'd be in terrible

strife without people telling us what's going on and why it's happening, and

why our reaction should be a certain way. That includes columnists of course.

"They're a wonderful thing,

something that newspapers have got over television. Television produces its

yellers and shouters, but newspapers have got their answer in the columnists.

Nobody quotes a television person as having an opinion. Look at the Sunday

Star-Times and its columnists! Marvellous bloody things when you add them all

together!" Have you got anything to say about

ending your column? "No," says Frank, "I'm not into curtain

calls." He once observed, in typically

provocative fashion, that "People shouldn't retire, they should just

die. You should die when you're not useful any more." He would still

believe it, and has some difficulty facing a disease that takes its own slow

time. His mother, he says, always envied people who dropped dead suddenly

because "they got away with not dying". |