|

|

North and South |

|

1 |

The Spence Case |

|

|

Cover Page |

|

2 |

When |

|

|

Introduction |

|

3 |

When

|

|

4 |

On

Frontline, Jeff and Louise's doubts were echoed by British experts, who

slated the work of therapists on the ward, claiming they had asked leading

questions to manipulate the child's answers. |

|

5 |

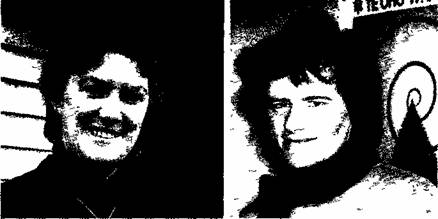

Television

cameras recorded the Spences' relief when charges against them were dismissed.

Jeff Spence's denials, and his distress, were achingly sincere. The next day,

the outcry began. |

|

6 |

The

Spences went back to living the rest of their lives in working-class |

|

7 |

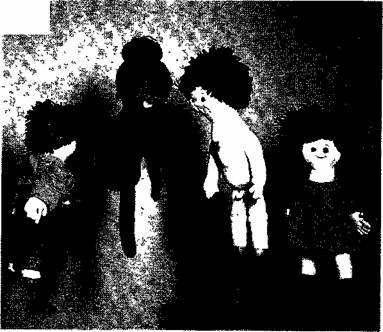

A

society newly asked to accept a massive incidence of child sex abuse within

its families, now had its own questions to ask: How could health

professionals be threatening the survival of families such as this on such

seemingly specious grounds? Who was to blame for the Spence story? How could

professionals be guilty of questionable behaviour? To whom were those

professionals answerable? And, most worrying of all, could any family with a

problem child suddenly face charges like these? |

|

8 |

In

all the outcry that followed, one remarkable fact emerged: the Spences, armed

against the inevitable worst that could happen, did not receive one offensive

phone call or abusive letter. |

|

9 |

Could this mean society has had

enough? |

|

|

|

|

10 |

LISELLE SPENCE is nearly six. She is

the dearly loved child of an extended family in which grandparents and aunts and

uncles play an active part. She is blonde and attractive to look at, and her

behaviour is at times beyond anyone's powers of endurance. Why that is so,

has defied experts for most of her life. |

|

11 |

Her

mother remembers puzzling that she never felt the child move before she was

born. Since her little brother Cory was born three years ago, Louise has had

several miscarriages, and wonders now if this has been because she was

carrying other daughters doomed to suffer from the disease that dominates

Liselle's life, tubrous sclerosis. The disease will

kill Liselle while she is still a young woman, and it means she must never

bear a child, because it would be severely retarded and probably die. |

|

12 |

Louise

first noticed that Liselle had fits when she was nine months old and started

crawling. By the time she was 14 months old, brain scans had revealed damage

to the left frontal temporal lobe of the child's brain, and experts decided

this was causing frequent epileptic fits. |

|

|

|

|

13 |

WHEN SHE was four, the Spences

took Liselle to |

|

14 |

One

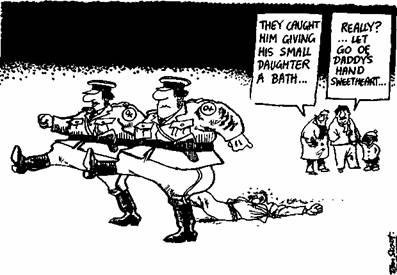

child in every 100,000 suffers from tubrous

sclerosis. The Spences have read everything they can find in medical

libraries about it and consulted everyone who can help. They know that

Liselle is unlikely to live past 30, and that the disease will doubtless in

time affect her kidneys, heart, lungs and eyes. |

|

15 |

Parents

of normal children will never know what it is to live with the strain of a child

suffering from a fatal illness, whose behaviour varies from the frightening

to the bizarre, yet who is loving, too. |

|

16 |

Liselle's

condition calls for endless vigilance. At 14 months, she had five serious seizures

in one day. When she started to walk, she fell constantly because of

epilepsy, and sometimes she is gripped by Todd's paralysis and can't walk at

all. That can happen when she has had too many seizures. Despite constant

medication, she still has about three seizures a day. |

|

17 |

Jeff

and Louise have become experts on more than 60 types of seizure, ranging from

the innocuous to the alarming. Right now, Liselle's front teeth are missing

because they smashed against concrete in the midst of an attack. Fragments

had to be removed under anaesthetic. |

|

18 |

The

stress of this is constant and will not end. It is small wonder that Louise

has shaken the child and screamed at her to stop in the middle of a seizure. |

|

19 |

Since

Liselle was two and a half years old, the Spences have received a handicapped

child's allowance of $22 a week, which pays for her to attend an early

intervention group for intellectually handicapped children. Every Thursday,

Louise has a helper from the Intellectually Handicapped Children's Society

for four hours. The family are longtime members of

the local Epilepsy Society. |

|

20 |

Epilepsy

causes one set of symptoms and behaviours; tubrous

sclerosis causes more. Liselle has the habit of repeating the last words

other people say to her at times. At other times she will do something

meaningless and repetitive like slam a refrigerator door shut 20 times in

succession until everyone around her is driven mad. She masturbates

compulsively and without inhibition, and removes all her clothing at whim.

She has tantrums of an epic scale which nobody can control. |

|

21 |

With

her three-year-old brother Cory she can be a demon. She cannot understand why

she must not climb into bed at night with him and wake him up. Louise and

Jeff have at times put her back in her own bed 30 times in one night. When

Cory was a baby, she frequently bit him, and herself, and she is still

sporadically violent. It is hard for Cory to sit and play alone and

concentrate, because she gets involved in his play and monopolises his

attention. Her own attention span is brief and erratic. |

|

22 |

When

she has her afternoon nap, and at night time, Liselle is still in disposable nappies

because she lacks bladder and bowel control in her sleep. Liselle dearly

wants to have her ears pierced and she's been promised that will happen when

she has not wet herself for a month. Nobody knows how far away that will be. |

|

23 |

It

is almost incidental that Liselle is mentally retarded. She's been assessed

at intellectually a year behind her peers, and her speech is poor, but

improving. Her slurred, hesitant and rather monotonous diction is a delight

to her parents because it gives them hope. |

|

24 |

This

is the child who was admitted to Ward 24 at |

|

|

|

|

25 |

KNOWING LISELLE would soon start

school, the Spences jumped at the chance to have her learn to be less of a

burden on teachers and themselves. They packed a suitcase and sent her to

live in at the ward, in a highly structured existence they were assured would

profoundly modify her behaviour. Sixteen hours later, workers in Ward 24 had

decided she was a suspect sexual abuse case. They did not tell her parents or

prepare them for the possibility of interviews that would follow,

endeavouring to find out for certain. |

|

26 |

From

the Spence family point of view, the six weeks on Ward 24 were fraught with

irritations and unexpected difficulties. Visiting relatives commented that

Liselle stank: the ward claims she never needed nappies while she stayed

there, but her family remembers the stink of stale urine and changing her

clothes because of it. They can not believe claims from the ward that Liselle

never suffered from an epileptic seizure while she was there, though this is

what staff reported. The Spences don't believe staff were competent to assess

the wide range of seizures they are used to, which can look as trifling as a

minute's blank inattention. |

|

27 |

Interestingly,

Liselle did not exhibit any strange sexual behaviour during her time in the

ward - neither removing her clothes, being sexually provocative, nor playing

in an overtly sexual way - all signals that would normally attract suspicion.

That behaviour took place only in private therapy sessions. |

|

28 |

There

were times of friction with Louise and the staff when she would arrive to visit

Liselle without prior warning and be told this was not convenient. Louise was

aware several times that Liselle was in a small, darkened room with a

counsellor, but the significance of this was not explained to her until the

six weeks had nearly ended. |

|

29 |

As

for Jeff Spence, he was working 14-hour days on a building site, which

limited the time he had available to visit his daughter. The ward staff did

not ask for an explanation of his infrequent visits and Louise believes they

concluded he was avoiding Liselle. |

|

30 |

Ward

24 is not talking about what happened to Liselle Spence. We do know that each

child admitted there is appointed a primary therapist to work with. Liselle worked

with Colleen Shaw and Karen Dennison. It fell to them to discover whether she

had been sexually abused. |

|

31 |

Karen

Dennison was Liselle's primary therapist. She was described in court as a registered

psychiatric and comprehensive nurse. This is likely to mean that she trained

under the new polytechnic system that involves identical training for all

nurses. It is less likely that she trained under the former system where

general nursing and psychiatric nursing were separated, with psychiatric

nursing being far more specialised. Nowadays, a nurse receives only about 12

weeks training in psychiatry in her three-year training; she is expected to

get practical experience on the job. |

|

32 |

Liselle's

senior therapist was Colleen Shaw. It was she who took primary responsibility

for the private sessions with the child which Dennison recorded. Shaw has a

Bachelor of Science degree in occupational therapy from the |

|

33 |

Shaw

had been with Ward 24 since it opened in March 1982, employed as a child

therapist working in developmental and behavioural problems, sometimes with

family groups. Like Dennison, she is unable to cite special qualifications in

the area of sexual abuse counselling or indeed psychological therapy

qualifications, which are by no means the same as occupational therapy ones. |

|

34 |

Shaw

had been involved previously with only three children who had been the

victims of sexual abuse. From her position of seniority over Dennison, we can

reasonably suppose Dennison had even less experience in disclosure

interviewing, a complex and subtle skill that carries a heavy burden of

responsibility for everyone involved. |

|

35 |

Suspicions

about Liselle were aroused in her first day on the ward when she made objects

out of playdough which she called "diddles". The objects were

round, and by the therapists' own admission did not resemble a penis, which

is what they were construed to be. The child cut up, sucked and licked the

"diddles". This aroused suspicion and steered her therapists

towards their sexual abuse theory. We can assume that this theory dominated

their concerns for the child, because the Spences report no behaviour change

of the kind they expected when Liselle returned home. |

|

36 |

Experts

agree that a child should be subjected to two disclosure interviews at the

most. Liselle was subjected to 18 private sessions of therapy (some lasting

longer than two and a half hours), 15 of which were disclosure interviews

aimed at uncovering her sexual abuse and its perpetrator. |

|

37 |

Workers

in the field all over the world disagree on the best methods of interviewing

and diagnosing abuse. In Ward 24, Shaw and Dennison used anatomically correct

dolls. |

|

|

|

|

38 |

THERE ARE many different kinds

of anatomically correct dolls, but they all have in common white or brown

cloth bodies with orifices such as mouth, vagina and anus that can be

penetrated. Adult male dolls have penises and testicles. Some dolls have the

sexual characteristics of children, and others look like naked adults,

complete with wool pubic hair and hair in their armpits. |

|

39 |

The

idea is that children will enact with the dolls what they have seen or

experienced. The only problem is that nobody knows what normal children do

with anatomically correct dolls. Nobody has bothered to carry out research to

tell us. Considering how graphically they vary from normal dolls, different

play seems inevitable. |

|

40 |

Anatomically

correct dolls, and certain interviewing techniques associated with them, are

used at |

|

41 |

Critics

say such confrontation can force a false answer from a child just as readily

as a true one. Just as in cases of cross-examination of rape victims, they

argue that the victim is twice abused, and they say children who have never

been abused are exposed to information that violates their innocence. |

|

42 |

It's

a method you would expect to be used with caution, close supervision by

superiors, and only in cases where there are substantial grounds for

suspecting abuse, such as physical evidence or a clear declaration by a

child. |

|

43 |

Liselle

never directly claimed she had been sexually abused, and it is clear that

Dennison and Shaw were not closely supervised by either peers or superiors. After

weeks of interviews, Ward 24 would find out that Liselle had no physical

signs of abuse, such as a damaged hymen. The child screamed and resisted an

internal examination, though her mother was in the room to support her.

Talking about it still makes Louise tearful. |

|

|

|

|

44 |

THERE ARE many pages of notes of

the disclosure interviews with Liselle. We can assume there are deficiencies

in these records, because tape recorders were not used and Dennison is not a stenographer.

We know that the therapists read the child a book called I Was So Mad I Could Have Split, a book used to help children

express anger against people they'd normally have difficulty challenging.

There are lines in the book like "I hate daddy", which Liselle

repeats. |

|

45 |

Early

on there was an important mistake. Liselle first met the anatomically correct

dolls when they were completely undressed rather than fully clothed as they

should have been. It is no surprise, then, that she concentrated on their

sexual differences. |

|

46 |

The

therapists' suspicions were further aroused not by anything Liselle said,

though she used the word "fuck" frequently, but by what she did in

early interview sessions. |

|

47 |

Liselle

picked up the sexually mature male doll, said "that's a big

diddle", then "don't bite the diddle", and chewed it. She

positioned herself in a sexually explicit way with the doll and seemed to

simulate intercourse. She talked about a fear of wild animals, which in court

would be construed as a simile for a male abuser. She referred to bleeding

bottoms - her grandfather had recently been operated on for piles. Liselle

talked about diddles and secrets in the dark. She talked about where she

played "diddle games" - at her own home and her grandparents'. She

was asked who was best at playing "diddle games", and talked about

both her father and grandfather. |

|

48 |

Some

of the sessions, which were not videotaped, involved Liselle being in the

dark with the therapists under blankets. |

|

49 |

You

could spend hours reading the transcripts and not make much sense of them.

You have to bear in mind that they involve work with a small child who is mentally

retarded and who you cannot be sure understands the intellectual concepts she

is dealing with. Though Liselle was tested when she was admitted to the ward,

the test was considered by one expert to be quite unsuitable for a preschool

child, and no other tests explored her intelligence and its limits before

therapists began working with her. |

|

50 |

There

is further doubt over whether Shaw and Dennison were briefed in any depth

over Liselle's physical problems. They are not recorded as having any knowledge

of the behaviour that can be expected of a child with both epilepsy and tubrous sclerosis, specialist knowledge that would not be

part of cither's training. |

|

51 |

A

week before Liselle was due to leave Ward 24, the therapists became concerned

that they were not going to get conclusive evidence that she had been abused.

They are on record as rewarding Liselle now for what they called "hard

work" by giving her jellybeans. Only now that they believed she would

name her father as her abuser did they tell Louise what they had been trying

to elicit for so long. They told her they were certain Liselle had been

sexually abused. |

|

52 |

Louise

remembers being stunned and shocked. She believed she was talking to experts who

must know what they were doing, and logically enough assumed Jeff must be the

perpetrator, since he was the only male with sufficient access to the child.

Shaw and Dennison then made an extraordinary request. They asked her to

return home for the next week with Jeff and not mention a word of these

suspicions to him or anyone else. This was too much for Louise. She told her

parents. |

|

53 |

Louise

was invited to watch the final sessions with the child, who the therapists

said was ready to tell her mother about her abuse. Louise watched a method of

therapy that she found shocking and revolting, therapy she would never have

countenanced if she had been told about it. But she was prepared to consider

it might be worth it if the truth was uncovered. |

|

54 |

Louise

saw Liselle pick up the daddy doll, say it was "the diddle man",

and throw it out the door of the room, returning to sit on a therapist's knee

and ask for a jellybean. The therapists felt they had the information they

needed to act on. |

|

55 |

The

Spences and their supporters suggest Liselle showed the behaviour you'd

expect from a child who'd been schooled to give the "right" answer

and rewarded for it with sweets. |

|

56 |

Jeff

Spence now came to the hospital for an interview with the therapists. They

told him they believed he had sexually abused his daughter and told him he

could not go home that night. If he did not leave home immediately, the

therapists said they would take steps to take Liselle away from her parents.

A bewildered and deeply upset Jeff went to stay with his in-laws, and so

began more than a year of spending nights away from his family while giving

the world the impression he was still living at home. |

|

57 |

Social

Welfare was not convinced by the report from Dennison and Shaw that Liselle

had been sexually abused, and refused to lay charges, but the police did. We

have no way of knowing who pressed for those charges, because Dr Watkins, the

ward's boss, only supported the assertions half-heartedly in court and

plainly had doubts. |

|

58 |

The

Spences - both Jeff and Louise - faced a complaint under the Children and

Young Persons' Act that Liselle was in need of care, protection or control in

that a) her development was avoidably being prevented or neglected and b) she

was being or likely to be neglected or ill-treated and c) she was exhibiting

behaviour which was beyond the control of her parents and was of such a

nature and degree as to cause concern for her wellbeing and her social

adjustment. |

|

59 |

The

charges seem strange because nobody has ever criticised Louise Spence's

affection for her child or her sense of responsibility for her. Apart from

the sexual allegation, nobody has ever criticised Jeff, either. |

|

60 |

The

Spences, who live off Jeff's earnings as a builder's labourer and freezing

worker, have twice paid their own way to |

|

61 |

What

the charges really meant was that the police believed they had a case to say

Liselle had been sexually abused, and that this in part explained her strange

behaviour. |

|

|

|

|

62 |

THE SPENCES have bitter memories

of their case being delayed and remanded seemingly indefinitely, while they

tried to face the fact that their family would be forced apart if the charges

against Jeff were believed by the judge. If the charges against Jeff were

sustained by Judge G.T. Mahon, he would certainly face proceedings under the

Crimes Act., his marriage would be over, and his family another failure

statistic. |

|

63 |

That

meant Jeff had to fight against the witnesses who accused him of sexually

abusing his daughter, and challenge their evidence. The Spences chose to

challenge the means by which Liselle's information was gathered, and its

truthfulness if those means were dubious. |

|

64 |

They

hired local lawyer Paul McMenamin who had

experience in defending child sex abuse cases in the criminal courts. This

was the first he had defended in the Children and Young Persons' Court, and he

was to have many misgivings about the system he now participated in. His bill

would exceed $20,000 and no one is yet sure how that will be paid. |

|

65 |

At

the same time the Spences contacted Frontline producer Peter Weir who became

interested in the story, and agreed to film the progress of their case and

its aftermath. He also approached two British experts who read transcripts of

Liselle's interviews and were outraged by them, a fact that gave the Spences

some comfort. The two experts were known in |

|

66 |

In

the final days of the case, the Spences hid Liselle with her grandparents

miles from |

|

67 |

At

the hearing the court heard Dr Watkins, the head of Ward 24, express

reservations about the case against Jeff. Watkins didn't think the

transcripts of the therapy session were conclusive enough, and he had doubts

about how Dennison and Shaw questioned Liselle. He was pretty sure Liselle

had some knowledge of sexual matters that was unusual, but could not be sure

how she came by it. He talked about the symptoms of Liselle's disease, which

included the very unsociable behaviour for which she'd been admitted to

hospital. |

|

68 |

Other

workers on the ward disputed the symptoms the Spences lived with, and claimed

not to have seen them during her six weeks on the ward. None was competent to

dispute her diagnosis, however, as only Watkins and another expert called by

the court, Dr Karen Zelas, had training as doctors as part of their

psychiatry qualifications. Unlike Watkins, Zelas was firmly on the side of

Dennison and Shaw, although she had only once met Liselle, in a 45-minute

session with her whole family. Despite this she was firm in her beliefs and

did not waver. When it came to arguing the toss, the strongest witness

against Zelas was Patricia Champion, a psychologist who had had dealings with

Liselle since she was 22 months old. |

|

69 |

Champion's

special area of expertise is language. She told the court Liselle's language

was not up to three-year-old standard, which meant that it was wrong to

expect a logical flow from her or to take it for granted that she was talking

from experience. She said Liselle's mind drifted aimlessly about and didn't

necessarily follow a logical train of thought, as the therapists might have

assumed it did. |

|

70 |

Zelas

was recalled after Champion gave evidence, and reaffirmed everything she had

said earlier, conceding nothing to the only other expert actively involved in

the case. She stuck with her belief that there was overwhelming evidence that

Liselle had been sexually abused. |

|

71 |

In

all of this, the judge was the final arbiter. He was critical of the number

of interviews Liselle had been subjected to and their method. He found that

Liselle's sexually oriented acts were clear evidence that she had been

sexually abused, and that there was nearly enough proof to lay a criminal

charge against a close family member, most likely her father, though there

was not enough proof that Jeff, and not another family member, had abused

her. |

|

|

|

|

72 |

IN ESSENCE, Judge Mahon said he

was satisfied Louise was now alerted to the fact that her daughter had been

sexually abused and that she would ensure that no further harm would come to

Liselle, and on that basis he dismissed the case. It was not what the Spences

could call an outright victory, but at least the family could stay together. |

|

73 |

Determined

that nobody else should have to go through their experience, the Spences went

ahead with the Frontline programme, rushed to air against the threat of suppression

by the Crown Solicitor's Office. Public interest was so great that it was

re-screened several days later and attracted an unprecedented flood of

letters, overwhelmingly supporting the Spences. |

|

74 |

You

would not have known this from |

|

75 |

Christchurch

Press reporter Cate Brett wrote a strongly worded feature criticising

Frontline for entering the volatile arena of child sex abuse and its

overworked and underqualified workers. She chided Frontline for not using the

complete inferences of Judge Mahon's judgment in full. Like others who

responded angrily to the programme, Brett implied that Judge Mahon's judgment

raised serious doubts about Jeff Spence's innocence. While that was true, it

is also true that the judgment shows serious doubts over the methods of the

professionals who worked with Liselle. |

|

|

|

|

76 |

IT WAS ALL too easy for the

Spence case to be reduced to whether a father was guilty or not of abusing

his daughter, a matter it was only for the court to decide. The questions raised

by the Spence case in fact incorporate every contentious issue in the field

of child sex abuse, and its repercussions are more complex than an individual

child's sad story. |

|

77 |

Those

questions concern a crusade that strikes to the heart of the family,

impressing on us that we are a society overrun with child sexual abuse that

must be uncovered and punished. The origins of the crusade are in radical

feminism, and its pioneer in |

|

78 |

Because

Saphira's findings are so influential and are the platform for a new set of

beliefs about ourselves, they deserve to be looked at again. They lead

indirectly to Liselle Spence's front door, because they have been the

foundation of the current intellectual climate regarding sexual abuse of

children. |

|

79 |

The

truth is, it's a subject that even experts know very little about. Those

experts are woefully thin on the ground, which doesn't stop people claiming

expertise and making claims they can't substantiate. |

|

80 |

Saphira

is a former Justice Department psychologist with an interest in sexuality.

She was formerly married, is a solo mother and is now a lesbian. Her adopted

name is a derivation of the name of Sappho, the

Greek woman poet from the |

|

81 |

In

1980, Saphira set up her Sexual Abuse of Children Project. She arranged to

enclose a questionnaire about sexual experience in every copy of one week's

New Zealand Woman's Weekly. In all, she sent out 220,000 questionnaires and

received 315 replies - a 0.14 per cent response - from women who described

sexual abuse in their childhood. |

|

82 |

The

findings of that survey have become part of the entrenched "facts"

of |

|

83 |

They

have helped to establish a climate of suspicion, and contributed to fears

that children are suffering because they cannot tell their story. |

|

84 |

Every

worker in the field fears that through their own lack of skill they may fail

to help a suffering child: much-quoted statistics lead them to believe sex

abuse is endemic. This fear may help create great stress in an already

difficult and distressing job, and it may also cloud judgment. |

|

|

|

|

85 |

THERE IS a political context

for this as well. In this decade, feminists everywhere have been challenging

the traditional behaviour of men and their abuse of power. High sexual abuse

data backs that up. It was disseminated by other influential feminists like

Hilary Haines of the Mental Health Foundation, another formerly married

lesbian, who published her own views under the aegis of the foundation. She

has cited Saphira's research frequently. |

|

86 |

Saphira's

findings are laid out in her book The

Sexual Abuse Of Children published in 1985. A skilled communicator,

Saphira makes an eloquent case for the prevalence of the problem and the harm

it can cause to children. In footnotes, she refers back to her own work under

her former name of |

|

87 |

Everyone

working in this field cites a 1984 survey by Wellington Rape Crisis in 1984, as

if it is very significant. This survey of 1100 high school students in |

|

88 |

Haines'

book Mental Health For Women

acknowledges assistance from established feminists like Pat Rosier, editor of

Broadsheet, and Margot Roth, a regular Broadsheet columnist. Broadsheet is

this country's outlet for radical feminism and its writers have a common

line. Though the Mental Health Foundation backed the book, it is more a

record of a feminist view of mental health than an impartial document. |

|

89 |

Haines

makes depressing reading on the subject of heterosexual sex. She records

nothing but problems and nowhere suggests that women have sex with men for

pleasure. "The reality is that, for many women, a man could pound away

till Christmas and all they would feel is sore and bored," she observes,

without citing any research to substantiate the claim. |

|

90 |

Lesbian

sex, however, is more hopeful. "Women understand each other's bodies

well," Haines says, "because after all they have one of their own,

and usually know how it works, so the sex is often better." |

|

91 |

It

was the Mental Health Foundation, where Haines worked, that sourced

"statistics" to last year's Telethon in support of families and children

at risk from violence and sexual abuse. Its data came from Saphira and its

own publications. |

|

92 |

On

the basis of that variously sourced information, which an over- keen

advertising agency conveniently blended together, New Zealand newspapers were

flooded with dramatic award-winning advertisements: photographs of four

little babies in nappies with the slogan "One of these children will be

scarred for life", alleging erroneously that one in eight fathers molest

their daughters; a little girl in bed with her teddy bear and the silhouette

of her father in the doorway with the slogan "It's not the dark she's

afraid of. |

|

|

|

|

93 |

FATHERS WERE suddenly the pits.

While mothers were rejoicing in a new interest and involvement of men with their

young children, in part due to grassroots feminism among heterosexual women,

New Zealanders were being asked to believe a lie: that one in eight of them

sexually abused their children. Incredibly, no one challenged this. Loving

fathers I met socially talked about their fear of cuddling their daughters,

in case they were accused of perversion. Though an editorial in this magazine

and a subsequent article in Metro exposed the false data, no serious attempt

has been made to eradicate the impression the campaign made - and it has been

subsequently quoted in other publications as fact. |

|

94 |

Most

people are not trained to understand statistics or the methodology of

research. There are, however, universally accepted ways of conducting

research that may lead to the truth. Those ways are expensive, cumbersome and

scientific, but without using them, nobody has the right to make claims for

the population at large. |

|

95 |

Saphira's

Woman's Weekly survey is a classic

case. The response rate from the circulars she sent out is so low that it

could be argued that only a little more than one in a thousand women

experienced sexual abuse as a child, an assertion that would explode all her

assertions. |

|

96 |

We

cannot know if the 315 people who replied to Saphira are anything like the

219,685 who did not, because they were not selected by truly random means. We

cannot know to which social class they belong, whether they live in cities or

the country, and what difference this might make. Everyone who did not read

the Woman's Weekly was automatically excluded from the survey, so it already

had a huge bias. |

|

97 |

To

back up her findings, Saphira turned to the classic study of sexuality, the

Kinsey Report. This work is almost half a century old, and its findings about

sexuality have to be set up against the incalculably greater amounts of

material on sex available for the general public to read and the changing

sexual patterns of even the last 20 years. Kinsey predates homosexual law

reform and the social acceptability of outspoken lesbians. |

|

98 |

Most

people writing and researching internationally in the field of child sexual

abuse agree that about one in 10 children may be affected by it. Even that is

a guess. Far fewer than one in 10 are abused by their own fathers, that is

certain. What surveys mean by sexual abuse varies from one researcher to

another. It's useless to pit one survey against another when the reference

points don't match, but that's what "experts" have been doing. |

|

99 |

Some

feminists consider a verbal overture to be an abuse. A radical feminist I

know considers it sexual abuse if a male has an erection in the presence of a

female who has done nothing to encourage him sexually. It is doubtful whether

the world at large would agree with her. |

|

100 |

We

have no way of knowing if the problem of child sex abuse is growing, because we

still have no reliable statistics on how frequently it happens. We know that

it has always been with us: that Victorian England knew child prostitution

and sent tiny children to work in factories and mines, that childhood itself

is a state only recently acknowledged, largely thanks to this century's

studies on human development. |

|

101 |

All

we know for sure is that our awareness of child sex abuse is currently

heightened in contrast with our awareness of child battering, the concern of

a decade ago and still a far more frequent occurrence. |

|

102 |

Some

social workers are worried that all the emphasis on sexual abuse cases, which

dominate Social Welfare services right now, is clogging the lines to help for

children who are in life-threatening situations. |

|

103 |

A

recent South Australian report (by Geoffrey Partington)

challenges all the information to date on who carries out sexual abuse on

children. The breakdown attributes one per cent of cases to mothers and siblings,

two per cent of cases to fathers, stepfathers and family friends, three per

cent to other relatives, 20 per cent to strangers, and an amazing 70 per cent

to professionals such as teachers and welfare workers. |

|

104 |

Figures

like these turn Saphira's work on its head. They suggest that the

"stranger danger" we've been told is a lie, may be the truth after

all. But swept away as we currently are on a tide of belief in the rottenness

of the heterosexual family unit, the truth could be the last thing we want to

hear. |

|

|

|

|

105 |

HOW DID WE come to accept that so

many |

|

106 |

Feminists

argue that men beat and abuse women because they believe they are lesser

human beings, and that they extend that behaviour to their children because

they believe they own them. They say men have everything to gain from

covering up their own unacceptable behaviour, so their denials and

questionings of the new data count for nothing. |

|

107 |

Feminists

and workers in this field say the abuse occurs at every level in society,

where you find men who believe in their inherent superiority and their right

to impose their will on others. Incest, they argue, is a natural extension of

patriarchal will. |

|

108 |

All

this does not explain why a male-dominated society has always had prohibitions

against incest, or why the typical sex abuser of children is a weak man who

doesn't rate highly in the world of male values - a failed patriarch rather

than a confident and successful one. Nor does it explain why men are afraid

to be found out. |

|

109 |

Repellent

though we find child sexual abuse to be, we know little about the harm it

does, except in gross cases of physical violation, which are still the

minority of cases. We do know that it is an abuse of power, and that

prostitutes, drug addicts and criminals report high rates of abuse in their

own pasts. However, in a cocktail of deprivations, we do not know which is

the deciding factor. |

|

110 |

Work

in child sex abuse is depressing and sometimes horrific. It outrages the

social code we live by and nobody approves of it. It is known to attract

workers who have been victims of abuse themselves, and some voluntary

organisations attract radical lesbian feminists. There is no reason why they

should be less competent at this work than anyone else, but their detachment

is questionable. |

|

111 |

Ms

Eileen Swan of Auckland's HELP, a sexual abuse counselling agency, is on

record in 1984 as saying "the projected figures of one in four girls and

one in 10 boys being victims are beginning to look conservative". She

has no more grounds than any lay person to say so; no hard evidence backs

her. |

|

112 |

Speaking

at a conference of the Child Abuse Prevention Society that year also, Sue

Neal, a coordinator of the South Auckland Women's Refuge, said "some of

these families are rotten to the core and should not be encouraged to stay

together". |

|

113 |

Again,

this may be how things look at the front, but statements like these are

worrying as a basis for looking at the problem. Swan's statistics might have

been snatched from thin air for all the foundation they have in serious

literature on the subject. |

|

|

|

|

114 |

THE SYMPTOMS of child sexual abuse

are a worry for any parent. One or other of them is displayed by normal children

at least some of the time: regressive behaviour, eating, sleeping and

elimination disturbances, excessive crying, excessive masturbatory behaviour

in small children, excessive attempts to manipulate others' genitals, school

problems, phobias, fears, lack of friends, secretive behaviour, stealing,

lying, manipulative behaviour... the list is long. Failing physical evidence,

when a child is too young to talk they're all case workers have to go on. |

|

115 |

This

is why we need experts in the field of child abuse. Experts can be expected

to know a great deal about normal child development. They can be expected to

be impartial and have profound knowledge of all the research and relevant

information in their field, with the ability to assess its usefulness. |

|

116 |

What

we actually have in this country are 11 child psychiatrists, two child

therapists graduating from |

|

117 |

All

of these workers are responsible to a professional organisation of some kind,

regardless of how minimal their qualifications are. The same does not apply

to voluntary workers. |

|

118 |

There

are no nationally accepted, universal training systems for people working in

child sex abuse. The closest we have is a part-time course at |

|

119 |

In

this burgeoning field, which some people call a growth industry, hardly

anyone can claim to be an expert, and those that do need close watching to

ensure they stay balanced. |

|

120 |

The

recent scandal in |

|

121 |

In

fact, nobody knew how often anal dilation occurred in the population at

large. It is a symptom of childhood constipation. Almost all of the children

are now back home with their distraught parents. |

|

122 |

Amazingly,

the male establishment in this country stood by and watched while workers

like Saphira produced their new data, and did not question it although they

recognised it for what it was - severely flawed and inconclusive. Three of

the highest child health and medical experts in this country confirmed this

to me, though they will not go on record officially as saying so. They've

said, that because they are men, they believe they will be shouted down. The

fact that they are experts too is held against them. |

|

123 |

Paranoia

runs so high that several people warned me that I must expect serious

physical attacks for asking questions against the prevalent feminist line. |

|

|

|

|

124 |

THE PUBLIC may want experts, but not

everybody in the field of sexual abuse does. Researching this story, two

senior health professionals told me about problems inside HELP. I was told

that workers there have argued against having heterosexual women with

children working in child sex abuse, on the grounds that they must therefore

have an interest in protecting abusive men. I was told about qualified women

doctors being turned away when they offered their services, on the grounds

that they were over-educated, which meant they must be part of the

patriarchal system. I was also told about mothers being turned away with

their abused children because they refused to report their husbands to the

police. |

|

125 |

Leah

Andrews, a recently graduated child psychiatrist, was denied assistance from

Auckland HELP for a much- needed study she is doing with another woman doctor

on the effects of sexual abuse on children. Andrews reports that HELP workers

were angry that the researchers received a financial grant, and told them

they should give the grant money to Maori and Polynesian women for projects

of their choice. Andrews found this behaviour hurtful and surprising; she

considers herself a liberal feminist. |

|

126 |

The

reason HELP gave for not helping the doctors was that they were from a medical

school and would therefore have a scientific approach. They were told that a

lot of harm had been done to women and children in the name of science. |

|

127 |

Andrews

has some reservations about statistics on sex abuse incidence. Looking for

subjects for her survey, she found that a number of children had been counted

several times by a variety of agencies. One child was recorded a total of

eight times, which would inevitably inflate statistics. |

|

128 |

Fellow

psychiatrist Jane Reeves has begun a private counselling group for rape

victims in |

|

129 |

Reeves'

view was that counselling should help women get over their rape rather than

reiterate their sense of helplessness. She also felt that women should be helped

to return to heterosexual sex if that was their preference, and wondered

whether radical lesbian separatists she knew were counselling in the field

were capable of that sort of help. |

|

130 |

"I

get quite angry at the anti-male flavour," Reeves says, "rather

than looking at specific males. After all, they are half the human race and

we have to function in society." |

|

131 |

Similar

criticism has been levelled at voluntary workers in child sex abuse, along

with doubts that their agencies give adequate supervision to their workers.

HELP has no national structure requiring national standards; each centre is

autonomous. |

|

132 |

Lack

of training, suspicion of expertise, scant resources, feminist activism and a

sudden flood of awareness of child sex abuse are the background to the Spence

case. The worry is that there may be many other cases like it. |

|

133 |

Feminists

fought long and hard to get acknowledgment for the problem. Having won their ground,

many behave as if the battle has to be fought still. Kingdoms have been made,

where workers zealously claim their right to monopolise society's view of the

problem. And everyone says they have the child's interests at heart. |

|

134 |

Right

now, our focus is on the men who sexually abuse children. In jail, we know

they are beaten and despised. Society feels like that about them, too. It's

not surprising that child sex offenders seldom confess, and will deny

fervently that they are guilty. They have everything to lose. |

|

135 |

We

know that many of these men were themselves abused as children, which is

another reason why we want to stop the chain of abuse by detecting cases now.

But are we going the right way about it? |

|

136 |

Police,

newly sensitive to the needs of the community, have faced criticism in recent

years for failing to prosecute wife beaters, or pursue rape cases with

sufficient diligence. Their sexism has been under attack. Now, police are

keenly aware of child sex abuse and actively involved in finding and dealing

with perpetrators. They're going to set up their own sex abuse teams in the

next year. |

|

137 |

The

courts in the meantime are clogged with sex abuse cases, which are proving

increasingly costly. A |

|

|

|

|

138 |

DAVID HOWMAN is a |

|

139 |

Howman is concerned that five per cent of cases in the

Children and Young Persons' Court are taking up 25 percent of the funding.

High costs are inevitable when sexual abuses cases are being fought over days

of hearings. |

|

140 |

There

are people working in the area who believe it would be better to bypass the

legal system altogether. Experience overseas has shown that when children are

interviewed expertly and recorded on video tape and the video tape is shown

to their abuser, he will often confess. This saves not only money but the

stress of putting children and their families through court hearings.

However, it also involves totally professional interviewing from experts. In |

|

141 |

At

the Justice Department in |

|

142 |

The

general idea is to offer child sex offenders a whip and a carrot at the same

time - and to keep them away from the criminal population, with which they

have little in common. |

|

143 |

Resources

in the justice system are woefully inadequate. Its psychological service has

32 workers in the field. They're expected to tackle more than 23,000

offenders with problems ranging from violent behaviour to chronic dishonesty

and suicidal impulses. "You've got to establish priorities," Riley

says. "Sex offending is a priority for our staff." |

|

144 |

In

the new jail, based on a successful American model, child sex offenders will

spend half their previously unproductive jail time hopefully learning how to

change. The Justice Department will keep records of how effective its

programme is. It's optimistic. |

|

|

|

|

145 |

THE SPENCE'S lawyer, Paul McMenamin, is a member of a family firm in |

|

146 |

"The

question of evidence is largely misunderstood by the lay public as technical

jargon to obfuscate issues, but in fact the rules of evidence are created to

arrive at the truth rather than a fallacy," he says. |

|

147 |

"In

these cases, what's before the court are records of interviews with little

children, taken under very peculiar circumstances. The children are not in any

usual or familiar environment. They're being interviewed by people in some

position of authority to them. Frequently comments are obtained by inducement

of one sort or another, and children I think have a great desire to please. |

|

148 |

"Frequently

people will say a child talks of things in a manner that's fearful or

distressed. There's no way a court can test that without videos. But even

videos may not finish the problem. The English experience indicates an

enormous amount of difficulty arises from enthusiasts who are frequently

quite well qualified. |

|

149 |

"If

an expert is very convinced that a child has been sexually abused, in the

absence of substantial physical evidence, too often the case relies on a

psychiatric or psychological appraisal of the child. All sorts of symptoms

and antisocial behaviour have been accepted as primary indicators, which you

could find in any child. Paper on paper has been written on this and they

tend to be flavoured by the view of the researcher." |

|

150 |

McMenamin is critical of experts who construe children's

statements, such as fear of wild animals, as something deeper and more

meaningful. "Like evidence-gathering," he says, "you can't

resort to a code that only you know." |

|

151 |

McMenamin says we are relying on the good sense of judges,

who are probably giving responsible and sensible verdicts. However, in cases

where experts are pitted against each other, usually we have a jury as our

safeguard. |

|

152 |

He

says the secrecy of these court proceedings is a worry. Though it is

considered vital to keep a child's identity secret, at the moment we cannot

also find information like how many child abuse cases are being heard, or

observe the manner in which investigations are being carried out. |

|

153 |

"I

personally can't see how 20 sessions of so-called therapy in semi- darkened

rooms with anatomical dolls, repetitive questions about sex, swearing and

shouting 'I hate daddy', can't be very dangerous for a child. I wouldn't

under any circumstances allow my four-year-old, or three-year-old or

two-year-old to go through that.. |

|

154 |

"I

simply cannot see how that child can't be left with an enduring aftermath. Is

this an abuse of power? |

|

155 |

"It

seems to me that the parents should have been advised at the very outset. I

can't see why or under what authority they deal with your child in a manner

contrary to the reason why it's in hospital. The point is, what right do

(hospital staff) have to do anything other than under your express direction? |

|

156 |

"Where

does an occupational therapist in a hospital obtain the right to involve a

child in what may be quite unusual sessions of conduct, which most people

would think abnormal and probably abhorrent, without obtaining the authority

of the parents? |

|

157 |

"Where

else but in a hospital could this happen? |

|

158 |

"If

this problem is as pervasive as people say and as enthusiasts would have us

believe, then people should be encouraged to admit it. We should remove the

criminal sanction and they should be treated. I've acted in criminal court

for people who've done this. They are invariably sad cases. And does jail

deter anyone?" |

|

|

|

|

159 |

I WAS UNABLE to visit Ward 24 or

talk with anyone there about its methods and philosophy. The hospital

hierarchy forbade it. However, I spoke to counsellor Sue Dick at its

outpatient arm, the Child and Family Guidance Centre. Twelve per cent of the

referrals here are because of child sex abuse. |

|

160 |

The

clinic's head, Dr Yvonne Barton, sat with her. Dick had chosen to speak to me

because she said she believes in the accountability of workers in her field.

She insisted the interview be tape recorded, as an insurance against being

misinterpreted and criticism from her fellow workers. |

|

161 |

Dick

is a former primary school teacher with a university degree, and is now a

trained child psychotherapist. She's a member of the New Zealand Association

of Child Psychotherapists. She told me the staff of the clinic is made up of

two child psychiatrists, three psychologists, three child psychotherapists

and eight social workers. |

|

162 |

Unlike

most workers in this field, Dick's training has involved personal therapy,

intended to help her self- knowledge and to help separate her own problems from

those of her clients. |

|

163 |

Dick

backs the need for recognised training in the field of child sex abuse

counselling, and says most health professionals in this country did their

training before sex abuse was isolated as a serious problem, so they have had

to train themselves. This raises the problem of who are the specialists or

experts. |

|

164 |

It

also raises the problem of what kind of safeguards clinics like this can have

so families get the best possible service and professionals are also accountable

to someone. |

|

165 |

Dick

said the clinic has a system whereby fellow workers watch therapy sessions

from behind one-way glass, so they can monitor how each other works and help

each other reach rational conclusions. Disclosure interviews are video-taped,

and before sexual abuse is suspected, therapists explore every other logical

avenue. |

|

166 |

"Children's

own relationship to the alleged offender varies enormously, from the child who

still loves them and wishes to keep a relationship, to children who are

damaged, angry, and hate the offender. Children can love and be attached to

the person who has abused them. The work you do has to preserve permission

for them to love that person. |

|

167 |

"We

feel very caught by the current status of legislation in terms of what it

does to families. We know that children want to be safe and have their

families intact - not one to the exclusion of the other. What we would like

is for children to be winners on both counts. |

|

168 |

"At

the moment, children are the losers, because if abuse is to stop they may

risk shattering their family. The best option would be for society to make it

possible for offenders to confess more readily. |

|

169 |

"We

don't want to get better at this [disclosure interviewing] only to enable

children to send their fathers to prison. What does it do for boys and girls

that for them to be safe their families are sentenced as well?" |

|

170 |

Dick

supports the idea of some child sex offenders - though not hardened pedophiles - receiving suspended sentences on condition

that they undergo therapy. |

|

171 |

She

told me that in |

|

172 |

Dick

acknowledges a great debt to Karen Zelas, the local psychiatrist who set up

the clinic and also gave evidence so forcefully at the Spence trial. |

|

173 |

Zelas,

now president of the Australasian Society of Psychiatrists, would not talk to

Frontline but was prepared to give |

|

174 |

Everyone

says Zelas is a convincing and articulate witness, and she has considerable

experience in child sex abuse. Her critics say she is unable to consider that

she may be wrong, but fellow professionals also consider her to be sound and

very capable. She was one of the panel responsible for the national report on

child sex abuse whose short title is A

Public And Private Nightmare. Interestingly, it endorses the use of

anatomical dolls. |

|

175 |

Ultimately,

professionals like Zelas have great power as professional witnesses in a

small society. There are only two psychiatrists in |

|

176 |

Like

Dick, Zelas told me she believed the courts were the ultimate organisation

she was accountable to and that she regarded the justice system as an

important safeguard. Like Dick, she is concerned to keep families together and

to find alternatives to jail for offenders. She believes the courts should

have the muscle to force men to enter therapy programmes and stay in them.

She also thinks men should have to pay for therapy for all members of the

victim's family that need it, and to do this they should stay in the

community and face up to their responsibilities. "Usually they don't

like what they're doing," she says. |

|

177 |

Zelas

says a 60 per cent confession rate among offenders in |

|

178 |

"It's

becoming more adversarial. You're starting to feel that you're sitting in a

criminal court. Lawyers most commonly in the criminal court are starting to

be engaged to help parents. The whole climate is changing. I don't think it's

desirable for civil matters involving children to start to become criminal

cases. |

|

179 |

"Standing

up even behind a screen in court is not exactly an environment likely to help

a child talk about something very private and personal, especially involving

a person they feel they must be loyal to." |

|

180 |

In

her own experience, Zelas says articulate middle-class offenders are much

less likely to go to court and less likely to be found guilty than men like

Jeff Spence, who know less about how to fight the system. "In social

settings, people will talk with me about feeling more uncomfortable about what

they do with their children than ever before. People say isn't that a

terrible thing. I think that is part of a pendulum swinging; it's not an end

point. |

|

181 |

"I

don't think people should stop doing ordinary affectionate things with

children, because there's a very small risk of being accused of sexual abuse. |

|

182 |

"Those

of us who do investigative interviews with children do have to be

accountable, and the courts need to determine what they consider to be acceptable

techniques. It's an issue that has to be resolved in some way." |

|

|

|

|

183 |

NOBODY WOULD be quicker to agree

with Zelas than the Spences, who feel bitter animosity towards her for the

evidence she gave in their court case. |

|

184 |

They

now have a child with all the problems they are familiar with, but also a new

preoccupation with sexual matters. They believe she has been mentally damaged

for life on Ward 24. Nobody from the ward has contacted them since Liselle

was discharged last May. Her family lives with the aftermath, and now the

only treatment Liselle receives is from a private psychologist they pay for

themselves - at $60 an hour, another burden to add to the as yet unpaid

$20,000 legal fees. |

|

185 |

Life

will never be the same and the Spences live in fear of further repercussions:

"I get worried sick that she might hurt herself. Say if she had a

seizure and busted her front teeth now - the slightest thing could get us

back in the courtroom," says Louise. Jeff worries that he may be the

only adult around to help a crying child, and end up accused of molestation. |

|

186 |

In

hospital recently, Louise met a nurse who had read the entire file on the

family and commented on it. The Spences say that when they took Liselle for a

brain scan in December, staff were rude and abrupt with them. They find it

humiliating that so many strangers have access to intensely personal

information about them, and say they would do anything to avoid going to |

|

187 |

They

are furious that Cate Brett asked them if they had been paid to appear on

Frontline, a question they found insulting. They were not. |

|

188 |

Most

of all, they are bitterly upset at changes they see in Liselle. "She

came out and she couldn't talk," Louise says. "Some of the things

she comes out with now - her sexual knowledge is unbelievable." |

|

189 |

Louise

is tense. She is the kind of person who might well sound angry when she is

feeling very sad. She does most of the talking, while Jeff defers to her.

From time to time he relaxes, though stress is apparent in him, too. |

|

190 |

In

their immaculate back yard, an enormous ginger cat whisks his tail and

parades in front of the family's aviary where two multicoloured parrots

perch. He looks for all the world like a small lion. "Perhaps he's one

of the wild animals Liselle's afraid of," Jeff Spence says, in his slow,

quiet way. |

|

191 |

It's meant to be a joke.

|

Appendix

|

Name |

Paragraph References |

|

|

|

|

Andrews,

Leah

...

. |

125,127 |

|

Barton,

Yvonne

|

160 |

|

Brett,

Cate

|

75,187 |

|

Champion,

Patricia

. |

68,69,70 |

|

Dennison,

Karen

...

.. |

30,31,33,34,37,43,44,50,52,57,67 |

|

Dick,

Sue

...

.. |

159,160-172,176 |

|

Ding,

Les

...

..

|

74 |

|

Haines,

Hilary

.

|

85,88,89,90,91 |

|

Higgs,

|

120 |

|

Howman, David

.. |

138,139 |

|

|

62,71,72,75 |

|

McMenamin, Paul

... |

64,145-158 |

|

Miller,

Amanda

|

3 |

|

Neal,

Sue

. |

112 |

|

Partington, Geoffrey

.. |

103 |

|

Reeves,

Jane

.. |

128,129,130 |

|

Riley,

David

. |

141,143 |

|

Rosier,

Pat

.. |

88 |

|

Roth,

Margot

|

88 |

|

Saphira

(Jackson), Miriam

|

77-86,91,95-97,104,122,175 |

|

Shaw,

Colleen

. |

30,32,33,34,37,43,50,52,57,67 |

|

Swan,

Eileen

... |

111,113 |

|

Watkins,

Dr Bill

... |

40,57,67,68 |

|

Weir,Peter..

. |

65 |

|

Zelas,

Karen

|

68,70,173-183 |