|

The

Christchurch Civic Creche Case |

|

|

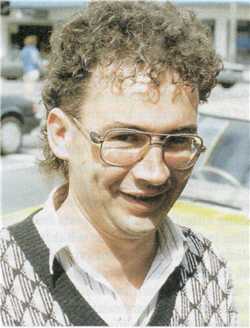

One Mother's Son Convicted child abuser Peter Ellis

has missed out on parole for the second time. But in May his case goes back

to the Court of Appeal, where new information will be presented, casting

further doubt on an already dubious verdict.

The curly brown hair has grown into a long ponytail, dyed

black - to hide the grey, his mum says, for Peter Ellis is 41 this week. In

the six years since he was locked up for abusing children at the Christchurch

civic creche he hasn't changed much otherwise; the sardonic twist to his

mouth is more pronounced, perhaps. He now sees so many vested interests at

work in his imprisonment that the world tightens into one focused conspiracy.

Or perhaps he is simply bitter that so many still feed off his case:

journalists, lawyers, officials, social-workers - at the end of the day they

can hop into the car, put the tape in the deck and go home. Peter Ellis expected to

be freed from jail the week before last. His case came before the National

Parole Board for the second time; he had refused to appear for the first.

This time he read a short statement: "I cannot accept any parole that

you could offer me because the board can only release me as a guilty

man." This was a gamble, because of course Ellis really wanted to be

free. "I wanted Peter to

do what he feels right about," said mother Lesley, while the parole

board was still thinking it over. "He's come so far. He has to stand

firm at this point, even if it means staying in jail. Of course he wants out,

but not at any price. The parole board says he must address his offending. He

says he hasn't any offending to address." The board refused to

release him, so now Ellis is serving, in effect, a voluntary sentence; he is

in the unusual position of electing to stay in jail. But the family is glum.

He wanted his freedom, and he, his mother and his lawyer Judith Ablett-Kerr

QC all expected him to get it. After all, he would be freed next February in

any event. Ellis started his sentence

in maximum security and the regime slowly eased over the years. His jail now

is one of the Leimon Villas, self-contained motel-like flats within

Christchurch's Paparua Prison, bright with the flowers Ellis has planted, the

kitten asleep on his bed and generally offering a better class of illusion,

but: "One gilded cage for another," he says.

When police first

arrived at Ellis's home in Tancred St, Christchurch, to arrest him, he was so

bewildered by the charges and read the warrant so slowly that police officers

had to jog him along. He said he was innocent then, during his 18 months of

trials and through six years in jail. When Ellis was

convicted, the Listener questioned thee jury's verdict. Had justice been

done? We didn't think so, although dozens of letters to the editor vilified

that view. Since then newspapers, magazines, TVl's Assignment and TV3's 20/20

have investigated the case and found it lacking. Even Ellis's parole board

took notice of the controversy, obliquely, by declaring itself unable to go

behind the jury's verdict and the judge's sentence. Public confidence in the

verdict has faltered. How could a case be

well-founded on the evidence of a steadily eroding number of children

describing tunnels and cages and knives and murdered children - a case

similar to the McMartin case in the United States, which was shown in a

television film here a few weeks ago? That is the question Ablett-Kerr is now

seeking to revisit. Ablett-Kerr was

approached after the Calder trial (the case of the poisoned professor) by

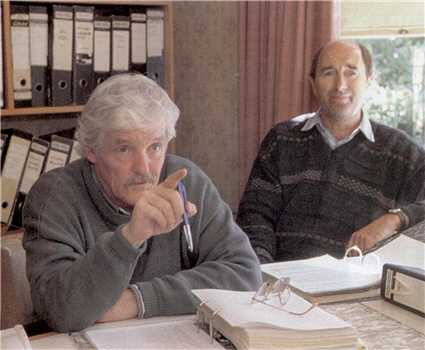

long-time Ellis supporters Winston Wealleans and Roger Keys, who are both

married to former civic creche workers, and who have built up a formidable

archive on the case over six years.

Says Ablett-Kerr:

"I was very reluctant. But they were very persistent." However, she

agreed to meet Ellis. The meeting evidently was convincing, for she took on a

case that had already passed through the hands of two QCs. Was there a single aspect

that made her decide that Ellis had been wrongly convicted? "I couldn't

see how it could have happened without someone knowing." The point has always

been troubling. Ellis was supposed to have abused dozens of children under

the noses of staff and parents for five years, without a single complaint. A

check of creche attendance records on a day picked at random by the Listener,

July 25, 1990, when the abuse was allegedly in full swing, shows that 31 kids

(including eight complainant children) were in the creche that day, with nine

staff and two students from the Christchurch College of Education. That day,

children were collected by 25 parents and six friends/relatives etc

designated by parents, some of whom spent some time in the creche. None noticed

anything amiss. The theory at the time, that Ellis in some way forced the

children's silence, still doesn't stack up. Four women who worked

with Ellis at the creche were initially charged with him. These women were

said to have encouraged Ellis by dancing in a circle, taking their clothes

off and pretending to have sex, watched by adults, including Lesley Ellis.

The naked children in the middle of the circle were told to kick each other

and were kicked in the genitals while the women laughed. One adult inserted a

needle into a child's penis. And more. On this kind of

evidence, Lesley Ellis came close to being charged herself. "I was

supposed to have hung the children, used the video camera to take

pornographic films, which they never found. Nor did they find the cages, or

the ladders. They searched my house, took a mask I'd got in Singapore, my

computer, my aerobics and basketball videos - they were so ordinary. I hope

they got really bored." The outcome for the

four women creche workers was far worse; they were charged - three of the

four on the evidence of one child - appeared in court, and were discharged

under a discretionary clause in the Crimes Act.

But the Court of Appeal

- despite one child recanting, and saying that she had lied - has already

rejected one appeal against his conviction by Ellis. Ablett-Kerr had to find

a new approach, and she decided on the risky and rarely successful one of

petitioning the Governor-General. She was successful. The Governor-General

referred the case back to the Court of Appeal, which will consider it again

at the end of next month. Ellis's new appeal will

rely heavily on evidence from Barry Parsonson, a consultant psychologist and

associate professor of psychology at Waikato University. At Ellis's High Court

trial, Justice Williamson began his summing up by framing the issue for the

jury to decide: do children lie? The defence said they did, the Crown said

they told the truth. The issue was critical, because a law change in 1985

made the uncorroborated evidence of children acceptable in court. Asked the same

question, Ablett-Kerr says carefully that, without referring to the Ellis

case, the answer was: "Of course. They're just the same as adults. There

are adults who tell lies and adults who tell the truth. And there, are

children who are mistaken." Parsonson turns to

other possibilities. He will testify that the interviews with the complainant

children were both flawed and risky, that parental interference contaminated

the children's evidence, the formal interviewing was suggestive, and the

"probability of the proportion of fact outweighing the proportion of

fiction must be very, very small indeed". He will argue that the

interviewing techniques would not be used today, and that children,

especially if they are under eight, are susceptible to suggestion in

recalling and reporting events. Parsonson will say that

the Court of Appeal, in rejecting Ellis's last appeal, did not appreciate the

full significance of Child A's recanting. One judge, Sir Maurice Casey,

declared it not uncommon for child complainants in sexual abuse cases to

withdraw allegations or claim they were lying, and that the judges were not

satisfied that the girl, in fact, had lied. Parsonson is to contest this.

Clinical studies, he will say, come to a different conclusion.

Ellis's new bid to

clear his name does not end there. Ablett-Kerr went back to the Court of

Appeal last year and asked for permission to argue the case over again. The

Court of Appeal told her to go back to the Governor-General. She did. In her

second petition she asked for either a free pardon or for the grounds of

appeal to be widened. Then she wants a royal commission into the whole

affair, for, says Lesley Ellis, that is what it will take to convince parents

and children: "It must be a nightmare for the ones who really believe.

They must say, 'Won't it ever go away, so we can get on with our

lives?'" Ablett-Kerr's new

petition went to the Governor-General late last year. And there it lay Until

New Zealand First MP Ron Mark jogged Justice Minister Tony Ryall's elbow with

a parliamentary question in February. Last month Ryall appointed a former

High Court judge, Sir Thomas Thorp, to investigate what he called the

"new and complex material" contained in the petition. Ablett-Kerr is pleased:

"The appointment of someone of Justice Thorp's stature to investigate

the matter is of real significance. We breathed a sigh of relief." So

did Lesley Ellis. "We're not going to get any better treatment from the

Court of Appeal than we did the first time unless she gets the inquiry

widened. Our main hope lies with the second petition, knowing someone better

[Thorp] is on the job."

The case began when a

woman, who had been abused as a child and who had a history of clinical

depression, became convinced that her child had been abused at the creche by

Peter Ellis. She questioned the child until eventually he talked of

"Peter's black penis". That curious observation became the genesis

of the affair. The child never gave evidence against Ellis; his evidence was

considered unreliable. His mother took him to another creche, where she

accused another male creche worker of abuse. The case sputtered into

life. A false start, then wham! Parents were being told that this would be

the biggest case of child abuse ever in New Zealand, that hundreds of

children could be involved. (More than 120 were interviewed, 21 gave evidence

at the preliminary hearing, 13 made it through to the High Court trial, Ellis

was found guilty of abusing seven of them and one of those told the Court of

Appeal that she had been lying.) Police and city council

officers now talk of the huge pressure from parents and on parents and

themselves, waves of allegations, panic, an apparent morass of abuse that

overwhelmed them all. Even the Ellises were caught up in it. Says Lesley:

"We just about had ourselves convinced at one stage. Peter said, 'They

say I'm in denial. Could I be?'" But, if Ellis was not

to blame, who was? In the 80s, the United

States saw an epidemic of satanic ritual abuse (SRA), kicked off by the

huge-selling Michelle Remembers, by Michelle Smith, a Canadian housewife, and

Lawrence Pazder, the psychiatrist who helped her to remember being tortured,

starved, sodomised, rubbed down with body parts and thrown into an open grave

with dead kittens by a satanic cult. The evidence, however, showed that she

was safely at school when all this happened. Soon after the book's

publication, the US child day-care centre scandals of the 80s erupted. Professor Mike Hill, a

Victoria University sociologist, believes that the creche case here, too, was

fired by the international pattern of satanic ritual abuse cases: "If

there'd been no SRA allegations, there'd have been no creche case." Hill has produced a

paper called Satan's Excellent Adventure in the Antipodes, tracing a troupe

of SRA experts from the US to Australia and ending in New Zealand in what he

calls "moral panic". Pazder, Michelle's saviour, went on to discover

satanism in the famous McMartin case, which started in 1983, when a mother

claimed that her son had been abused by the only male worker at the McMartin

day-care centre. As the case gathered momentum, it threw up two key

investigators, social worker Kee MacFarlane and psychiatrist Roland Summit. MacFarlane introduced

the anatomically correct dolls to insistent children's interviewing that

searched for "truths". Summit's "pseudoscientific" ideas,

says Hill, became enshrined in the dogma "believe the children",

and the maxim that children never lie about abuse unless they are recanting. Two other players in

the McMartin case were David Finkelhor and Astrid Heger. Finkelhor discovered

some 36 ritual abuse scandals in the US in the early 80s, even if no arrest

or conviction followed. Allegations, though, proliferated amid what Hill

calls "hysteria". Finkelhor subsequently produced the

"bible" for ritual abuse believers, Nursery Crimes. Heger

popularised diagnostic techniques, later discredited; her belief that sexual

abuse could be detected by the size and shape of young girls' hymens became

an abuse indicator in the investigation at Christchurch's Glenelg Health

Camp. The original mother's

complaints in the McMartin case became more and more bizarre. She was

eventually diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic and died soon after of

alcohol poisoning. Charges against five women defendants in the case were

dropped. The remaining woman was found not guilty. After two trials, charges

against the male defendant were dismissed. But McMartin set a pattern. Two other American

social workers enter the picture: Pamela Klein, whose set of satanic

indicators became influential in several countries. They included

bed-wetting, fear of monsters and ghosts, preoccupation with faeces etc. And

Pamela Hudson, who produced a set of satanic symptoms that surfaced in the

Christchurch creche case, including being locked in cages, buried, tied

upside down or hung from hooks, participating in mock marriages, seeing children

killed, having blood poured over them and being taken to churches and

graveyards for ritual abuse. Summit, MacFarlane,

Heger and Finkelhor all addressed the 6th International Conference on Child

Abuse and Neglect in Australia in 1986. In 1988, a mother

claimed sexual abuse by a "Mr Bubbles" at a Sydney day-care centre.

The case was similar to McMartin. Children claimed to have been abducted,

drugged, assaulted with knives, hammers, pins, sexually abused, filmed for

pornography and forced to watch animal sacrifices and satanic rituals.

Involved in interviewing children was a Sydney psychiatrist, Dr Anne

Schlebaum, who saw an international satanist conspiracy, which she described

to a 1990 conference of the Australia and NZ Association of Psychology, Psychiatry

and Law. The Mr Bubbles case fizzled, but similar cases sprang up in other

states. Schlebaum went on to

advise New South Wales MP Franca Arena, who alleged a major suppression of

evidence against paedophiles, orchestrated by leading politicians and judges.

The resulting inquiry did not agree. The satanic cult

scenario, says Hill, was introduced to New Zealand in May, 1990, when Pamela

Klein spoke to a child sexual abuse conference here. The following year the

Ritual Abuse Group (Rag) was formed in Wellington, receiving public funds.

The group circulated material, including Pamela Hudson's, on satanic cult

allegations and Christchurch became the focus. Two conferences were held in

quick succession in 1991; at a major family violence prevention conference,

Rag presented a paper arguing that ritual abuse should be accepted, not

discounted, and promoted a list of symptoms chillingly similar to those that

emerged in the later creche case. Late in 1991, the first

allegations against Ellis were made. Hill notes the

similarities to cases in the US and Britain, including the circle incident.

Crown prosecutor Brent Stanaway managed to suppress most of the more bizarre

allegations in the Christchurch creche case. But they lurked in the

background during the case and afterwards; this reporter, and others, were

invited by police to view the range of satanic connections, which, they said,

only expedience had excluded. The mother of the child

who later described the circle incident (and listed all 16 of Pamela Hudson's

satanic indicators) even demanded that Hudson be brought to New Zealand as an

expert witness. (Hudson did conduct a workshop here after the trial,

involving creche parents and others who were then Department of Social

Welfare staff.) In her book A Mother's

Story, which she writes under the name Joy Bander, the mother agrees that she

questioned her child closely, despite warnings not to. He talked of being

drugged, of photographs being taken, children being hurt, being stuck with

needles, of being thrown down traps, of the circle and "horrific"

abuse there, about killing a boy, of women pretending to have sex. The mother, who quotes

Hudson extensively, went on to do a good deal of research into satanic ritual

abuse. She clearly believes it implicitly and for a time produced a

newsletter on the subject. "Bander" refused to be interviewed for

this article. But she did say that, although many things had changed since

the case, one thing had not: Peter Ellis was guilty. "We were right, the

court was right and he's inside." And she believed her son.

The Accident

Compensation Commission (ACC) at the time paid lump sums of $10,000 to sexual

abuse victims. There were more than 60 claimants in the case; the ACC paid

out more than $500,000. The Christchurch City

Council ran the creche, and closed it as the scandal grew. It paid out

$180,000 - in counselling to parents, redundancies and other payments - then

fought a case through the Employment Court (which awarded the redundant

creche workers more than $lm) and the Court of Appeal (which cut back the

payment to $170,000). The justice system,

even in a climate where debunking verdicts has become a growth industry, has

taken a battering. Justice Williamson is now dead, but lived to see the

verdict he so roundly agreed with come under increasing pressure. Eight Court

of Appeal judges have sat either on the Employment Court appeal or the two

Peter Ellis hearings. Politicians have jumped

this way and that. Prime Minister Jenny Shipley was Minister of Social

Welfare when her department was presiding over the case; John Banks, after

declaring Ellis to be "walking evil", changed his mind after the

20/20 programme and declared the evidence against Ellis to be "falling

apart". The then Social Welfare

Department interviewers and other specialists now see their work publicly

derided. Police have been

accused of mishandling the case and have even seen a leading detective on it

accused of mispropriety with creche mothers after the trial. A subsequent

police investigation found that Detective Colin Eaade had suffered from stress,

but was not psychologically incompetent and his indiscretions had been minor. Parents who believe

that their children were abused, children (whether abused or not) and most

people involved feel muddied by a case that, as one counsellor remarked to me,

"taints everyone it touches". In Christchurch, it

remains one of those defining issues. You are either for Peter Ellis or

against him, and the rifts are bitter and enduring. One of the lawyers who

defended Ellis told friends he was 95 percent convinced that Ellis was

innocent, but 100 percent convinced he should not be in jail. (I put this

equation to Ablett-Kerr and asked where she stood. Ever cagey, she replied:

"Ask my friends.") In court, Ellis often

seemed the forgotten figure, as posses of reporters, police, lawyers, parents

and experts sniped at each other. I've met Peter Ellis. We don't get on very

well, but that's not important, because the only question here is still the

one that ended the Listener's story in 1993: beyond reasonable doubt? |